In 1857 the Union Steam Ship Co., founded in 1853 as the UNION STEAM COLLIER CO., tendered successfully to carry the mails between England and South Africa. For the next 15 years its ships, almost all with “Tribal” or “National” names e.g. DANE, NORMAN, ROMAN, etc., carried out this duty to the satisfaction of the governments concerned and most of the general public, so much so that two shipping companies, first the Diamond Line (1863) and then the Cape of Good Hope Steam Navigation Company (1867), which tried to rival its services to the Cape, soon faded out. A third company, the East India and London Line, might have proved a more worthy competitor to the Union Line as its ships from 1862 called at the Cape on their way to or from India and their home port, but by 1865 it, too, had ceased operations. When the discovery of diamonds in the Cape stimulated trade yet another firm tried to compete with the Union Line, namely the Cape and Natal Steam Navigation Company (1870). Several of their early ships suffered shipwreck or engine breakdowns, but in April 1871 their ship SWEDEN broke all records by reaching the Cape in 27.5 days from Dartmouth, the Union Liners then still taking 38 days for the passage. Two months later their WARRIOR did the trip in 27 days. Moreover, this new concern charged only £31.10/- for a first class ticket between England and the Cape, compared with the £42 charged by the Mail Company.

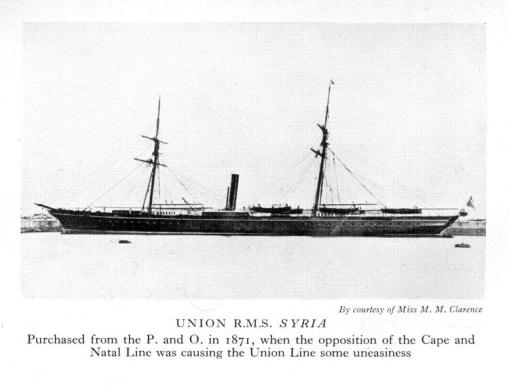

The Union Line reacted to this challenge by buying the P & 0 Liner SYRIA (of 1 959 tons, built in 1863), a much finer vessel than any that had yet appeared on the Cape run which, on her second voyage in Union Line colours, came out from Southampton to Table Bay in 26 days 18 hours. The Mail Ship Company also reduced its fares to the same level as its opponent’s. For its first sailings the Cape and Natal Company had relied on chartered ships, some of which were not as successful as the two record-breakers, while they waited for the completion of their own ships, the KAFIR, GRIQUA, ZULU and FINGOE, all 1 500-tonners being built on the Clyde. Before these could enter service, however, the line had gone bankrupt, the chartering of ships having proved too expensive.

The Union Line reacted to this challenge by buying the P & 0 Liner SYRIA (of 1 959 tons, built in 1863), a much finer vessel than any that had yet appeared on the Cape run which, on her second voyage in Union Line colours, came out from Southampton to Table Bay in 26 days 18 hours. The Mail Ship Company also reduced its fares to the same level as its opponent’s. For its first sailings the Cape and Natal Company had relied on chartered ships, some of which were not as successful as the two record-breakers, while they waited for the completion of their own ships, the KAFIR, GRIQUA, ZULU and FINGOE, all 1 500-tonners being built on the Clyde. Before these could enter service, however, the line had gone bankrupt, the chartering of ships having proved too expensive.

Yet this Company introduced to the Cape trade one who soon became its best-known personality. Born in 1825 in Greenock, Donald Currie was a ship-owner and a ship-broker. He agreed to take over the chartering of ships for the Cape and Natal Line and so, in January 1872, sent two of his ships, first the ICELAND and then the GOTHLAND, both 1 500 tons, built in 1871, for the rival service to the Cape. While they were away, however, Currie was told that the charterers were unable to meet the expenses of these voyages, so Currie decided to run the vessels for his own account. This venture proved so successful that Currie agreed to the suggestion of various merchants in London and the Cape to continue in the Cape Trade. He had since 1860 been running a service between London and India via the Cape with a number of fine 1 200-ton iron-built sailing ships, especially for bringing back to England jute produced in India. These ships all were named after CASTLES. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had a disastrous effect on this trade, as jute could be transported by even the uneconomic steamers of those days far more profitably via Suez than by the long haul round the Cape; so Currie needed little persuasion to enter the lists against the Union Line. He had already ordered four steamers for his Indian service, DOVER CASTLE and WALMER CASTLE (2 300-tons, built by Barclay Curle) and EDINBURGH CASTLE and WINDSOR CASTLE (2 600-tons, built by Robert Napier and Sons). While they were completing he chartered a number of other ships to run under his houseflag, one of which, the PENGUIN (1871; 1 741-tons) on 2 May 1872 arrived in Table Bay after a record-breaking passage of just under 25 days.

Yet this Company introduced to the Cape trade one who soon became its best-known personality. Born in 1825 in Greenock, Donald Currie was a ship-owner and a ship-broker. He agreed to take over the chartering of ships for the Cape and Natal Line and so, in January 1872, sent two of his ships, first the ICELAND and then the GOTHLAND, both 1 500 tons, built in 1871, for the rival service to the Cape. While they were away, however, Currie was told that the charterers were unable to meet the expenses of these voyages, so Currie decided to run the vessels for his own account. This venture proved so successful that Currie agreed to the suggestion of various merchants in London and the Cape to continue in the Cape Trade. He had since 1860 been running a service between London and India via the Cape with a number of fine 1 200-ton iron-built sailing ships, especially for bringing back to England jute produced in India. These ships all were named after CASTLES. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had a disastrous effect on this trade, as jute could be transported by even the uneconomic steamers of those days far more profitably via Suez than by the long haul round the Cape; so Currie needed little persuasion to enter the lists against the Union Line. He had already ordered four steamers for his Indian service, DOVER CASTLE and WALMER CASTLE (2 300-tons, built by Barclay Curle) and EDINBURGH CASTLE and WINDSOR CASTLE (2 600-tons, built by Robert Napier and Sons). While they were completing he chartered a number of other ships to run under his houseflag, one of which, the PENGUIN (1871; 1 741-tons) on 2 May 1872 arrived in Table Bay after a record-breaking passage of just under 25 days.

The first of his new ships completed was the DOVER CASTLE but, just before she was to sail for the Cape, she was chartered by the Pacific Steam Navigation Company to take a sailing to South America from Liverpool. On her return trip from Callao in Peru she suddenly caught fire. Her captain (belonging to the P.S.N. Co.) decided to take her into Coquimbo where she was scuttled. The EDINBURGH CASTLE was also taken up on charter to South America and spent several months in that trade. The WALMER CASTLE on her first voyage went on to Mauritius after her call at the Cape, while the WINDSOR CASTLE actually did two voyages to India (via Suez) before entering the Cape trade in which she broke the Cape record (in May 1873) by coming out in a quarter of an hour more than 23 days.

In view of this successful opposition the Union Line asked the British Government to extend the life of their contract, scheduled to expire in 1876, to 1881, guaranteeing to cut the time per trip to 30 days instead of 38. In view of the success of the Castle Line this caused such an outcry in both Britain and the Cape that this proposal was rejected. Meanwhile the Cape Government in 1873 offered to give the Castle Line £150 for every day that its ship took less than the 30 proposed by the Union Line. Thus, when in 1876 the mail contract between England and the Cape was to be renewed the Government divided it between the Union and the Castle Lines, each line to send a mail steamer to the Cape on alternate weeks. This also had the effect of giving the Cape for the first time a weekly mail service with England.

It was this arrangement also which brought the term “Intermediate Steamer” into the vocabulary of people in the Cape. It became the custom for each of the mail companies to send one of its ships, usually the older and smaller ones, to take sailings in the week when the other mail company supplied the mail steamer, and these ships were spoken of as “Intermediate Steamers”. Later on, when the mail steamers began growing steadily in size, it was realized that the Intermediate Steamers did not need to be so fast nor so big as the Mailships, as they did not have to work to a definite schedule. Also it was realized that the smaller and slower steamers could be used on routes other than the official mail route when trade so demanded.

The first ships specially to be put into the Intermediate service (i.e. not former mailships) were the Union Line’s DANE and ROMAN in 1889 and 1890. The former had been built in 1870 as the AUSTRALIA for the P & 0 Line, the latter as the NILE also in 1870 but for the R.M.S.P. These ships were needed because of the great expansion of trade between Britain and South Africa as a result of the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886. They were both found to be unsuitable to the Cape Trade, the former being sold for scrap after only a year’s trading; the latter lasting until the Union Line’s first specially-built intermediates were completed in 1894.

The first ships specially to be put into the Intermediate service (i.e. not former mailships) were the Union Line’s DANE and ROMAN in 1889 and 1890. The former had been built in 1870 as the AUSTRALIA for the P & 0 Line, the latter as the NILE also in 1870 but for the R.M.S.P. These ships were needed because of the great expansion of trade between Britain and South Africa as a result of the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886. They were both found to be unsuitable to the Cape Trade, the former being sold for scrap after only a year’s trading; the latter lasting until the Union Line’s first specially-built intermediates were completed in 1894.

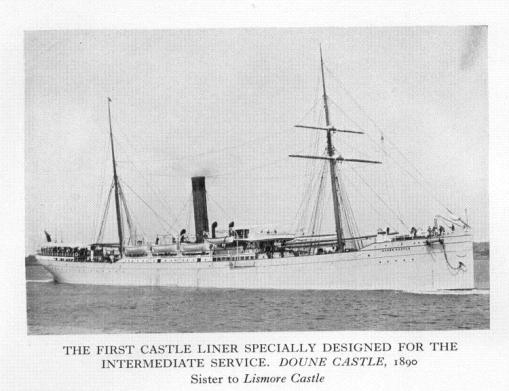

Meanwhile the Castle Line had also decided to put specially-built ships on the intermediate service. The first pair coming out as the DOUNE CASTLE (1890) and LISMORE CASTLE (1891), identical sisters of 4 046 tons. They first carried passengers in 3 classes.

Meanwhile the Castle Line had also decided to put specially-built ships on the intermediate service. The first pair coming out as the DOUNE CASTLE (1890) and LISMORE CASTLE (1891), identical sisters of 4 046 tons. They first carried passengers in 3 classes.

Soon after this the Union Line invited Mr (later Lord) Pirrie, head of the famous Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, to visit South Africa and study conditions at all our seaports so as to design and build ships suitable for them. The first fruits of his visit was the coming to the Cape of the first of the “G” group of intermediates, the GAUL, GOTH and GREEK in 1893. They were twin-screw steamers, the first so fitted for the South African run, able to carry much cargo and yet have a draught of water small enough to enable them to cross the bars at East London and Durban so as to berth alongside the Quays, with extremely good passenger accommodation. Ships of about 4 750 tons each, they were bigger than all the Cape mail ships of the time except the DUNOTTAR CASTLE (1890; 5 625 tons) and the SCOT (1891; 6844 tons).

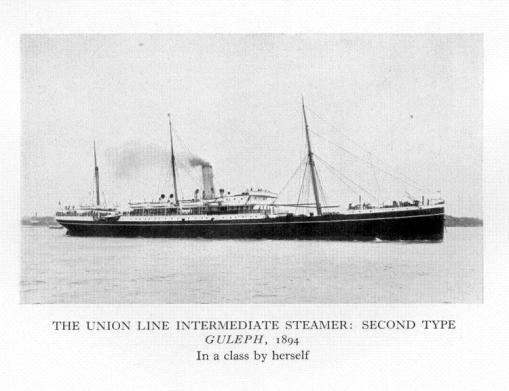

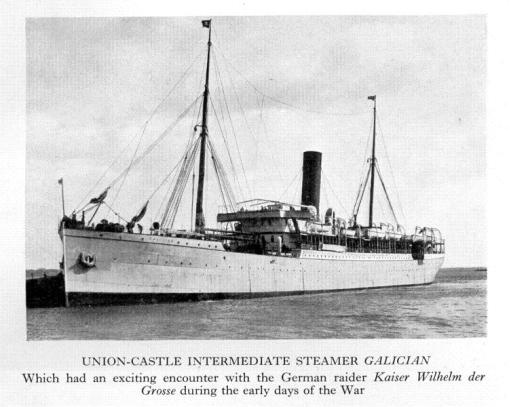

They were followed in 1894 by a modified sister, the GUELPH (4917-tons), differing chiefly in having three masts instead of two. Three years later came another trio (GASCON, GAIKA, GOORKHA) which could best be described as enlarged GUELPHS, of about 6 300-tons each; and these were followed by the last trio, very similar but slightly larger, which reverted to a two-mast rig, the GERMAN (1899), GALEKA (1900) and GALICIAN (1901) of approximately 6 770 tons each. The last-mentioned actually never came out in the Union Line colours (black hull with white riband at upper deck level, red below water line, white upperworks, buff-coloured funnels, brown masts) as when she was completed the two lines had already amalgamated, when all the ships of the new Union-Castle Line were given Castle Line colours.

They were followed in 1894 by a modified sister, the GUELPH (4917-tons), differing chiefly in having three masts instead of two. Three years later came another trio (GASCON, GAIKA, GOORKHA) which could best be described as enlarged GUELPHS, of about 6 300-tons each; and these were followed by the last trio, very similar but slightly larger, which reverted to a two-mast rig, the GERMAN (1899), GALEKA (1900) and GALICIAN (1901) of approximately 6 770 tons each. The last-mentioned actually never came out in the Union Line colours (black hull with white riband at upper deck level, red below water line, white upperworks, buff-coloured funnels, brown masts) as when she was completed the two lines had already amalgamated, when all the ships of the new Union-Castle Line were given Castle Line colours.

This magnificent fleet of intermediates completely outclassed those of the Castle Line, after whose original pair came the HARLECH CASTLE (1894; 3 634-tonnes) which was interesting as she was fitted to carry only first and third class passengers, a system which later became standard among the intermediates and also among the last mail ships, although with them it was called First Class and Cabin (or Tourist). She and her two predecessors were sold in 1904.

This magnificent fleet of intermediates completely outclassed those of the Castle Line, after whose original pair came the HARLECH CASTLE (1894; 3 634-tonnes) which was interesting as she was fitted to carry only first and third class passengers, a system which later became standard among the intermediates and also among the last mail ships, although with them it was called First Class and Cabin (or Tourist). She and her two predecessors were sold in 1904.

In 1895 came the ARUNDEL CASTLE, of 4 588 tons. She set a short lived fashion for the Castle Line of a  four-masted rig with her one funnel. Like all her predecessors she crossed yards on her foremast in case of an accident to her single screw or its engine. She was followed by two slightly enlarged sisters, TINTAGEL CASTLE (1896) and AVONDALE CASTLE (1897), twins of 5 531 tons. In 1897 also came another pair of sisters, but with only two masts, very similar to the original DOUNE CASTLE and LISMORE CASTLE of 1890: the DiJ1′–1(-)1 I.Y CASTLE (4 157 tons) and RAGLAN CASTLE (4 324 tons). These latter two, however, were designed to carry a considerable cargo on a light draught in order to be able to cross the bars at East London and Durban. They carried only 35 first class and 100 Steerage passengers.

four-masted rig with her one funnel. Like all her predecessors she crossed yards on her foremast in case of an accident to her single screw or its engine. She was followed by two slightly enlarged sisters, TINTAGEL CASTLE (1896) and AVONDALE CASTLE (1897), twins of 5 531 tons. In 1897 also came another pair of sisters, but with only two masts, very similar to the original DOUNE CASTLE and LISMORE CASTLE of 1890: the DiJ1′–1(-)1 I.Y CASTLE (4 157 tons) and RAGLAN CASTLE (4 324 tons). These latter two, however, were designed to carry a considerable cargo on a light draught in order to be able to cross the bars at East London and Durban. They carried only 35 first class and 100 Steerage passengers.

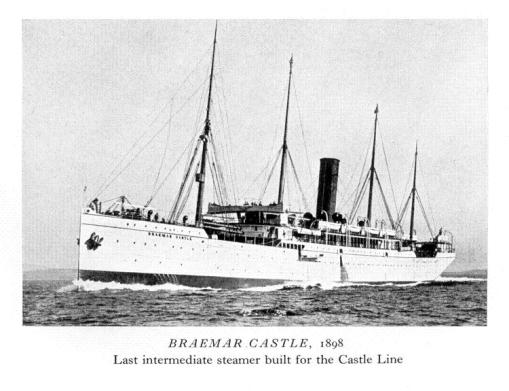

The last intermediate liner built for the Castle line was the BRAEMAR CASTLE (1898; 6266 tons) and the only one that could be compared with the ten fine intermediates of the Union line. Like them she carried her boats on a boat-deck above the promenade deck amidships; but she suffered from the disadvantage of still being a single-screw ship. She was the first Castle intermediate ship without yards on her foremast. She was also the only one of these Castle liners to be used for a considerable time in the Cape service. (The DOUNE, LISMORE, HARLECH CASTLES were sold in 1904; the* ARUNDEL CASTLE in 1905, the AVONDALE and TINTAGEL CASTLES IN 1912). The BRAEMAR CASTLE served the company and her country well in peace and in war. In October 1915 she became a hospital-ship, struck a mine in the Eastern Mediterranean in November 1916 but managed to get to Malta where she was repaired. In 1918 during the Allied Campaign Bolshevists she became “Base Hospital” in Murmansk, with her decks boarded in to increase her capacity and to keep out the cold. Her curious appearance then led to her acquiring the nickname of “Noah’s Ark”. After about a year there she became a troop-transport. In June 1920 she resumed her place in the intermediate service, but after only one voyage was again requisitioned as a troopship and sent out east to India and China, and again in 1922 when there was trouble in Turkey. She was eventually scrapped in 1924. I can well remember her leaving Cape Town for the last time in 1920. I was a boy of fourteen and my father had taken us up Table Mountain. While we were children we always were taken up via Platteklip Gorge. I can remember that when we reached the top and were resting I turned, as always, to look over the sea and the docks, and saw this four-masted one-funnelled ship leaving the harbour. Because my friend Marischal Murray had for some years been giving me postcard pictures of ships, including just about every ship in the Union-Castle line, I was pretty sure it was the BRAEMAR CASTLE, and the next day in the shipping news in the “Cape Times” I saw her name in the “Departures” column. But I did not realize then that she would never again visit Cape Town. One other point that should be noted about the BRAEMAR CASTLE was that she was the first Castle intermediate to have her first class accommodation amidships and not aft, where it had always been in the sailing-ships and so also in the early steamships. The Union Line intermediates had this feature, and the boat-deck amidships raised above the upper (promenade) deck, since the first “G” class ships appeared in 1893.

The last intermediate liner built for the Castle line was the BRAEMAR CASTLE (1898; 6266 tons) and the only one that could be compared with the ten fine intermediates of the Union line. Like them she carried her boats on a boat-deck above the promenade deck amidships; but she suffered from the disadvantage of still being a single-screw ship. She was the first Castle intermediate ship without yards on her foremast. She was also the only one of these Castle liners to be used for a considerable time in the Cape service. (The DOUNE, LISMORE, HARLECH CASTLES were sold in 1904; the* ARUNDEL CASTLE in 1905, the AVONDALE and TINTAGEL CASTLES IN 1912). The BRAEMAR CASTLE served the company and her country well in peace and in war. In October 1915 she became a hospital-ship, struck a mine in the Eastern Mediterranean in November 1916 but managed to get to Malta where she was repaired. In 1918 during the Allied Campaign Bolshevists she became “Base Hospital” in Murmansk, with her decks boarded in to increase her capacity and to keep out the cold. Her curious appearance then led to her acquiring the nickname of “Noah’s Ark”. After about a year there she became a troop-transport. In June 1920 she resumed her place in the intermediate service, but after only one voyage was again requisitioned as a troopship and sent out east to India and China, and again in 1922 when there was trouble in Turkey. She was eventually scrapped in 1924. I can well remember her leaving Cape Town for the last time in 1920. I was a boy of fourteen and my father had taken us up Table Mountain. While we were children we always were taken up via Platteklip Gorge. I can remember that when we reached the top and were resting I turned, as always, to look over the sea and the docks, and saw this four-masted one-funnelled ship leaving the harbour. Because my friend Marischal Murray had for some years been giving me postcard pictures of ships, including just about every ship in the Union-Castle line, I was pretty sure it was the BRAEMAR CASTLE, and the next day in the shipping news in the “Cape Times” I saw her name in the “Departures” column. But I did not realize then that she would never again visit Cape Town. One other point that should be noted about the BRAEMAR CASTLE was that she was the first Castle intermediate to have her first class accommodation amidships and not aft, where it had always been in the sailing-ships and so also in the early steamships. The Union Line intermediates had this feature, and the boat-deck amidships raised above the upper (promenade) deck, since the first “G” class ships appeared in 1893.

Of these fine “G” class ships the first four were also sold fairly early, the GREEK and the GOTH in 1906 and the GAUL and the GUELPH in 1912; but the others lasted until at least the first World War (when the GERMAN was renamed GLENGORM CASTLE and the GALICIAN the GLENART CASTLE for obvious reasons) and except for the GALEKA (sunk by mine off Cape La Hogue, October 1916, while serving as a hospital-ship) and the GLENART CASTLE (ex GALICIAN, torpedoed by U56 in the Bristol Channel, 26 February 1918); they lasted until the late twenties , the last to be sold being the GLENGORM CASTLE (ex GERMAN) in 1930. I remember these ships very well; my favourite was always the GAIKA! They were an extremely successful and popular class.

Of these fine “G” class ships the first four were also sold fairly early, the GREEK and the GOTH in 1906 and the GAUL and the GUELPH in 1912; but the others lasted until at least the first World War (when the GERMAN was renamed GLENGORM CASTLE and the GALICIAN the GLENART CASTLE for obvious reasons) and except for the GALEKA (sunk by mine off Cape La Hogue, October 1916, while serving as a hospital-ship) and the GLENART CASTLE (ex GALICIAN, torpedoed by U56 in the Bristol Channel, 26 February 1918); they lasted until the late twenties , the last to be sold being the GLENGORM CASTLE (ex GERMAN) in 1930. I remember these ships very well; my favourite was always the GAIKA! They were an extremely successful and popular class.

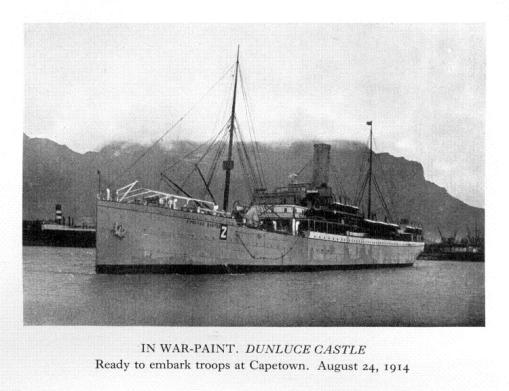

The UNION LINE and the CASTLE LINE were amalgamated in February 1900 while the Anglo-Boer War was in progress, in which most of the ships so far mentioned carried many troops and supplies for the Imperial Army in South Africa. After the war there was again an upsurge in trade and so in 1904 new intermediate liners were needed, especially as several of the former Castle intermediates were being sold. Three new liners were ordered for this service, the Durham Castle, DOVER CASTLE and DUNLUCE CASTLE, in design very much enlarged editions of the GERMAN of 1899. They were of about 8 200 tons and thus bigger than two of the ships. in the mail-fleet, the NORMAN (1894; 7537 tons) and the CARISBROOK CASTLE (1898; 7 626 tons);-they were faster than the previous intermediates, having a service speed of 14 knots as against 12. They had extremely good accommodation for some 350 passengers in first and third class, spacious promenade-decks for ships of their size, and were fairly steady ships. The first two were built on the Clyde, the last by Harland and Wolff, Belfast.

The DOVER CASTLE and her sisters ran in the Intermediate Service of the Union-Castle Line for 10 years without any mishaps, but on 16th March 1914 the DOVER CASTLE when approaching Port Elizabeth hit the Roman Rock (now called Despatch Rock) and had to be emptied of much cargo, while passengers were transferred to GALWAY CASTLE for passage to Port Natal.

The DOVER CASTLE and her sisters ran in the Intermediate Service of the Union-Castle Line for 10 years without any mishaps, but on 16th March 1914 the DOVER CASTLE when approaching Port Elizabeth hit the Roman Rock (now called Despatch Rock) and had to be emptied of much cargo, while passengers were transferred to GALWAY CASTLE for passage to Port Natal.

The DOVER CASTLE from August 1914 took some voyages in the Mail-service (several of the mail-steamers having been requisitioned to serve as Armed Merchant Cruisers) but a year later was refitted as a Hospital-ship. While serving as such in the Mediterranean she was on 26 May 1917 when 60 miles north of Bona, torpedoed without warning by UC67. The torpedo-explosion killed six stokers, but everyone else aboard was saved by other ships. Her sisters did good work during the 1st World War, the DUNLUCE CASTLE also as a hospital ship, the DURHAM CASTLE mainly on the mail-run. After the War they speedily became the most popular ships in the intermediate service until 1931, when both of them were placed  on the Round-Africa service of the Company. Their time on this service was mostly uneventful, except that in April 1936 the DURHAM CASTLE struck a submerged object off the Zululand coast and had to return to Durban to have several of her bottom plates renewed. They were sold for scrapping in mid 1939, but both were rescued by the Admiralty which, seeing that War was again looming, took them over to serve as R.N. depot-ships. The DURHAM CASTLE was on tow to Scapa Flow in January 1940 but while off Invergorden was sunk by a mine or torpedo. The DUNLUCE CASTLE served as a depot-ship throughout the War and was scrapped soon after it ended. These three ships resembled those of the GERMAN class but had their bridges “set back” from the forward end of the boat-deck, also had more massive funnels with a very noticeable rim around the top.

on the Round-Africa service of the Company. Their time on this service was mostly uneventful, except that in April 1936 the DURHAM CASTLE struck a submerged object off the Zululand coast and had to return to Durban to have several of her bottom plates renewed. They were sold for scrapping in mid 1939, but both were rescued by the Admiralty which, seeing that War was again looming, took them over to serve as R.N. depot-ships. The DURHAM CASTLE was on tow to Scapa Flow in January 1940 but while off Invergorden was sunk by a mine or torpedo. The DUNLUCE CASTLE served as a depot-ship throughout the War and was scrapped soon after it ended. These three ships resembled those of the GERMAN class but had their bridges “set back” from the forward end of the boat-deck, also had more massive funnels with a very noticeable rim around the top.

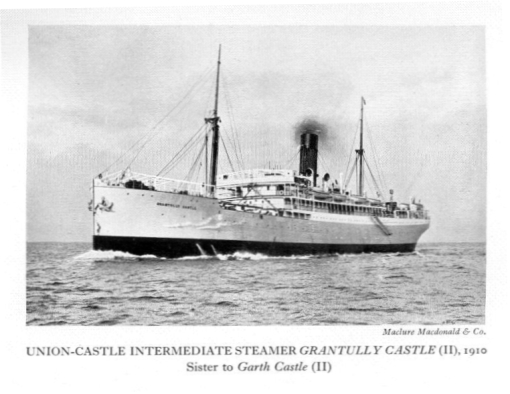

There was an interval of six years before new ships were needed for the intermediate service. Then two new ships were ordered from Barclay Curle and Co. on the Clyde, the GARTH CASTLE and the GRANTULLY CASTLE, of about 7 620 tons. IF, design they were very similar to the DURHAM CASTLE class but had thinner funnels and the bridge in the normal position at the forward part of the bridge-deck. They differed also in having passengers in three classes: 100 first class, 100 second class and 200 third class. They were followed in 1911 by three enlarged sister, GLOUCESTER CASTLE, GUILDFORD CASTLE and GALWAY CASTLE, all of just under 8 000 tons. They were two feet longer and two feet broader than their two predecessors, and had their bridges a deck higher to have a short extra promenade deck at the fore-end of the boat deck. It was easy to pick them out from their two predecessors as No. 1 boat on each side was raised above numbers 2, 3 & 4. These three ships also served the company well and also their country in the First World War

There was an interval of six years before new ships were needed for the intermediate service. Then two new ships were ordered from Barclay Curle and Co. on the Clyde, the GARTH CASTLE and the GRANTULLY CASTLE, of about 7 620 tons. IF, design they were very similar to the DURHAM CASTLE class but had thinner funnels and the bridge in the normal position at the forward part of the bridge-deck. They differed also in having passengers in three classes: 100 first class, 100 second class and 200 third class. They were followed in 1911 by three enlarged sister, GLOUCESTER CASTLE, GUILDFORD CASTLE and GALWAY CASTLE, all of just under 8 000 tons. They were two feet longer and two feet broader than their two predecessors, and had their bridges a deck higher to have a short extra promenade deck at the fore-end of the boat deck. It was easy to pick them out from their two predecessors as No. 1 boat on each side was raised above numbers 2, 3 & 4. These three ships also served the company well and also their country in the First World War

First to appear at the Cape was the GLOUCESTER CASTLE on the 15 September 1911. She served in the normal intermediate service until 6 August 1914 when she was requisitioned by the British government as a troopship, taking men of the Expeditionary Force of the British Army to France. She remained on this cross-channel run until May 1915 when she was fitted out as a hospital ship. She then returned to the cross-channel service with an occasional trip to the Mediterranean. On 31 March she was torpedoed by a U-boat in the Channel with the loss of three lives, but fortunately was towed into Southampton and repaired. Then until the end of the war she remained in Red Cross work in the Channel, going to the Mediterranean still as a hospital ship after the Armistice for more than a year, returning to the Union Castle’s Intermediate Service only in the latter part of 1920. A year or two later she was put into the “Round Africa” service but in 1926, when the new LLANDAFF CASTLE was completed, she resumed sailings in the West Coast Intermediate Service for which she had been built. This continued until 1938 when she was laid-up at Netley after having been replaced by the newer 17 400-ton intermediates DURBAN CASTLE and PRETORIA CASTLE.

In September 1939 on the outbreak of war and the consequent requisitioning of several Union-Castle Liners for government service she was again brought into the England-South Africa run. For three more years she did good service, but in July 1942 she disappeared. For some time nothing was learnt about her fate, but in 1943 news of “survivors” was received, which showed that she had been sunk. The details of her sinking, however, were not known until after the final victory in August 1945.

On 15 July 1942 the GLOUCESTER CASTLE en route for Cape Town, was about 1 300 miles south east of Freetown. The ship being in the tropics, the weather was hot and sticky with many sudden showers. When night came the ship was “blacked out”; about 19h00 there was a sudden bright flash fairly close by on the starboard bow, and at almost the same time an explosion on the GLOUCESTER CASTLE, just below the starboard bridge wing. More shells followed along with pom-pom and machine-gun fire. The radio hut was demolished, the operators killed, the aerials shot down; so there was no possibility of any “S.O.S.” or “Raider” warning messages being sent. All the boats on the ship’s starboard side were destroyed or badly damaged. It was possible to launch only one boat from the port side. So sharp and sudden was the attack that the ship sank after only about ten minutes. Many of these aboard her had been killed by the gun fire, more by drowning. Of her complement of 154 only 61 were saved; these included 4 of her 12 passengers. Those saved, apart from those who managed to get into the boat that survived, were picked up by a motor boat from the GLOUCESTER CASTLE’S assailant which turned out to be a disguised German merchantmen armed as a raider. She was a new cargo ship launched after the outbreak of the war as the BONN, but taken over by the German Navy almost immediately as the MICHEL (Schiff 28, on the German Navy List). Of about 5 000 tons she carried a number of 5.9″ guns, all on mountings disguised as normal cargo ship fittings; also several small quick-firing and machine-guns. The survivors were all taken in a captured tanker to Singapore, where many of the deck- and engine-crew and stewards were put ashore to work for the Japanese. The rest were taken to Japan, where they were put ashore at Yokohama, after a bad trip of three months in the tanker. But their experiences on shore as Japanese prisoners working in the Osaka docks were much worse, where up to 78 prisoners had to sleep in one room on mats which, like the woodwork, were riddled with bugs, fleas and lice. They were forced to work, rain or shine, in carrying heavy loads of timber on their shoulders for distances of half a mile, over mud and water, and beaten savagely if they faltered or were late. This they had to endure until Japan capitulated in August 1945. Before this, however, in October 1943, the MICHEL had been sunk by an American submarine.

The GUILDFORD CASTLE was the next of the trio to reach Cape Town, on 11 November 1911 (11-11-11). She served in the normal Intermediate Service until August 1914, when she formed part of the Convoy of Union Castle ships which carried the former Imperial garrison of soldiers back to England where they were added to the “contemptible little army” (as the Kaiser called it), which at Mons stopped the German advance on Paris. Then she was refitted as a hospital ship, first in the Mediterranean and Indian services, later off the coast of German East Africa –(Tanganyika) where South African, British and Indian units were capturing Germany’s last African colony She took sick and wounded men from East Africa to Durban, Cape Town or on to England. On one such trip, when in the Bristol channel bound for Avonmouth, she was attacked by a U-Boat. Fortunately, the first torpedo fired at her missed, and the second, which hit her, failed to explode. She was much luckier than her sisters! After this she was used as a cross-channel hospital-ship. This continued even after the Armistice, and it was only in 1920 that she returned to the intermediate service. Like the GLOUCESTER CASTLE she was for a time used on the “Round Africa” service, but returned to normal service after the LLANGIBBY CASTLE was completed in 1929. She met her end in Germany in the Elbe River on 1 June 1933 when, through the fault of a German pilot, she collided with the motorship STENTOR and was sunk. Two people were killed in the collision but fortunately there was no other loss of life.

The GALWAY CASTLE, the last of the three to arrive in Cape Town (19 Nov. 1911) was the first to be lost. Like her sisters she ran in the intermediate service until the outbreak of the War in August 1914. Her first duty was to take South African troops to “German West”, carrying many thousands of them between Cape Town, Luderitzbucht and other South-West African seaports. When this service was over she became a mail-steamer. She had one unpleasant experience while on this run when near Gull Light-Vessel on 3 August 1916, she was attacked by a German plane which dropped several bombs which, fortunately, all missed her.

Just over a year later (12 October 1917) she ran ashore on the Orient Beach in East London. She was not damaged and was refloated a few days later; but while there she provided a spectacle for East Londoners and was much photographed. Eleven months later the GALWAY CASTLE under the command of Captain Dyer left Plymouth with a full complement of passengers (346 civilians plus 400 invalided South African troops). When two days out from Plymouth she was torpedoed by U82. The torpedo hit just forward of amidships and broke her back. The ship became hogged and it seemed that she might break in two at any minute. Everyone was mustered on deck and the ship’s boats were lowered as soon as possible. Owing to the large number of people on board (nearly a thousand all told) it was difficult to get them all into the boats, especially as the break in the ship’s decks amidships made it very difficult to communicate between people in the forward and the after parts. As a result some 150 people died. Actually there was no need for haste, as in spite of her severe wounds the ship did not sink for three days. So disappeared the last U-C ship to have been built under the regime of Donald Currie. Incidentally she was the only one of the “G CASTLES” which was not taken up as a hospital ship and the only one which ran regularly for some years in the mail. The next two ships were built in 1914 when the Union-Castle Line had been brought into the great R.M.S.P. Co. group run i by Lord Kylsant. They were the first LLANDOVERY CASTLE and the LLANSTEPHAN CASTLE. They actually appeared under the designation of “Royal East African Mailships”, as they were the first ships designed and built for the mail-service from England via the Mediterranean and Suez to British East Africa. They were of 11 400 tons and thus much larger, not only than all the preceding Intermediate liners, but also than five of the mail-steamers (NORMAN, BRITON, CARISBROOK CASTLE, KILDONAN CASTLE, KINFAUNS CASTLE). Their appearance was far more like the “A” steamers of the R.M.S.P. Co. at that time than like any other ship in the Union-Castle Line. Their passenger accommodation was far superior to that in any U-C vessel on the West Coast service.

The LLANDOVERY CASTLE left London early in 1914 and visited several East African ports before turning round in Durban. When she reached Mombasa on her return trip she found her younger sister, LLANSTEPHAN CASTLE, there on her maiden voyage. The meeting of these two ships, easily the largest and finest of the East Coast run, was a splendid advertisement for their owners. She however, did only two trips on this east cost service as, when she arrived back after the second, the First World War had broken out, several Cape Mail steamers had been requisitioned as Armed Merchant Cruisers, so she was transferred to the West Cost Mail Service. In Dec 1915 she was requisitioned as a troopship, but in July 1916 refitted as a hospital ship. She did occasional trips to Canada in this guise, but on 27 June 1918, when homeward bound from Halifax, N.S., she was torpedoed at 9.30 pm by U.86, 114 miles West of Fastnet Rock. There were 258 people aboard the ship, which was brilliantly lit and with illuminated red-crosses to show what she was. Most of those aboard were able to get into boats and leave the ship, which sank in ten minutes. But the U-Boat surfaced and proceeded to shell the boats, killing most of their occupants. When the destroyer H.M.S. LYSANDER arrived at the scene at daybreak she found only one boat with 24 survivors. This was one of the worst atrocities of the U-Boat campaign in the 1914-18 War.

The LLANSTEPHAN CASTLE had completed only one voyage in the East African service when war broke out. She was transferred to the West Coast mail-service in which she ran until 1917. I well remember her leaving Cape Town soon after the war began, as my cousin was aboard, on his way to Oxford University and, as the ship was being pulled away from the quay, he threw a shilling down to me to catch, which I did not, being only 6 years old at the time. In 1917 all ships were requisitioned by the Shipping Controller so the normal Cape Mail Service came to an end. She became a troopship mainly in transatlantic service, but after the Armistice again joined the Cape Mail Service until 1920, when the last of the requisitioned mailships had rejoined the fleet. She then returned to the service for which she had been built, which soon because the “Round Africa” service. For many years she ran in that service and, although larger ships were built for it, she remained one of the favourite ships because of her great amount of deck space and fine accommodation

Soon after the Second World War broke out in 1939 the LLANSTEPHAN CASTLE was requisitioned. She was, however, usually sent to the Cape. In August 1940 she carried a group of 300 children, aged 5 to 15 to Cape Town, to get them away from the bombings in London. Nearly a year later, June 1941, the LLANSTEPHAN CASTLE started a new career for which she was not well-suited, joining the convoys which carried supplies from Britain to Russia via the Arctic Ocean. On the first of these convoys she was the Commodore’s ship. Fortunately the Germans had evidently received no news about this convoy, so the ships reached Archangel safely on 1 September. They stayed there for nearly a month and on 28 September, joined by 8 Russian vessels, they started their return trip. The LLANSTEPHAN CASTLE carried 200 Polish airmen who had been prisoners in Russian hands for nearly two years. On October the convoy reached the Clyde safely and the Polish airmen joined the R A F.

A year or two later she was taken over by the Royal Indian Navy and served in the Burma campaign and later in the then Dutch East Indies. Fortunately she had been converted to oil-burning shortly before the war, so her radius of action had been increased

After the war she was refitted for the Round-Africa service in which she served until 1952. Thus she had served for 38 years, including two world wars and throughout had remained a favourite with passengers. Thus there was widespread regret when she was sold for scrap. I was travelling in the DURBAN CASTLE to England when we passed the LLANSTEPHAN CASTLE on her last trip, so there was much hooting and cheering!

Three other “LLAN” ships served in the Union Castle Line before the Second World War. In December 1925 the second LLANDOVERY CASTLE arrived in Cape Town. Designed to take the place of her sunken namesake she was a slightly smaller and slower ship, built to carry some fifty fewer passengers. She did not have the wide promenade decks that were such a prominent feature of her predecessor, and it was probably because of this that neither she nor her sister LLANDAFF CASTLE which was completed early in 1926, was as popular as the earlier Three years later the last of the “LLANS ” appeared, the LLANGIBBY CASTLE of 12 000 tons. She was really just an enlarged sister to the original pair but was a motorship, the first to appear in the intermediate fleet of the Union-Castle Line, and the first in the “Round Africa” service. Built by Harland and Wolff of Belfast, but in their shipyard at Govan, Glasgow, she was, as Marischal Murray points out in his book “Ships and South Africa”, built for an English firm by an Irish Company in Scotland and with a Welsh name! She was the finest of the “LLANS”, perhaps not in looks but certainly in the luxury of her cabins, wide deck space and speed. In appearance she resembled the mailship CARNARVON CASTLE of 1921 except that her boats were slung above deck-level as in the mailships WINCHESTER CASTLE and WARWICK CASTLE, which appeared a few months after she did. She became exceedingly popular in the Round Africa service and also in the West Coast intermediate service. She carried 450 passengers in two classes.

She had an eventful life during the war (1939 – 1945), taking part in many dangerous convoy trips. In January 1942 she was a unit in a convoy rushing troops to Singapore. She had 1500 of them on board. In the morning of January 16, four days after leaving Britain, she was hit on her stern by a torpedo, which destroyed her rudder , blew her stern gun overboard and killed 26 men. The weather was bad, a strong wind blowing and the waves were high. Captain R.F. Bayer was instructed to make for the Azores independently, in itself a very dangerous move. Fortunately neither of the propellers had been destroyed so the ship could be steered, although with great difficulty, by “jockeying” the screws. Three hours later the LLANGIBBY CASTLE was again attacked, this time by a long-range plane which dropped bombs, which fortunately missed, and by machine-gun fire which wounded the ship’s bosun. The vessel’s A.A. guns hit back and the attacker was hit and made off with black smoke streaming from it.

It took the LLANGIBBY CASTLE three days to cover the 700 miles to the Azores, but on January 19 she reached Horta Bay, where the Portuguese authorities gave the ship 14 days in which to make repairs. There were no proper repairing facilities at Horta, nor were any of the troops nor the ship’s company allowed ashore (except for the captain, on business!), but all hands enjoyed seeing the lights and having the ports of their cabins open, after the normal “black-out” conditions in Britain and at sea.

Meanwhile the R.N. was making arrangements to succour the ship. On February 1 three destroyers and an Admiralty tug arrived, to escort the LLANGIBBY CASTLE on the next stage of veritable battle occurred, with U-boats that had been waiting for the liner and escorting destroyers fighting it out with guns, starshells, depth-charges and torpedoes. Meanwhile the LLANGIBBY CASTLE had been having trouble in steering, , so she was taken in tow by the tug. After daylight she cast off the tug and again proceeded under her own steam, steering a rather “wobbly” course which, however, served as the necessary zig-zags which were compulsory for ships in submarine-infested waters! The destroyers managed to keep the U-Boats at bay until four days later, when land was sighted and the tug again took the liner in tow. On 8 February she anchored safely at Gibraltar, where her passengers were disembarked to wait for another vessel. Then followed a long period of just over 8 weeks at Gibraltar while decisions were being made in high quarters about the vessel’s future. It was found impossible to replace the ship’s rudder, so apart from some strengthening of her stern she was in much the same state as before. Finally she was ordered to return to Britain. This last haul of nearly 1500 miles was done safely in six days, the ship steaming by herself except for a few hours in the Straits of Gibraltar when she was towed by the tug. In all she had steamed about 3400 miles without stern or rudder and got through it all safely, which must be a record!

After full repairs she resumed service as a troopship and was one of the great armada that brought Allied soldiers to French North Africa in November 1942. In the early hours of 8 November she was hit by an 8″ shell fired from a shore battery which destroyed the Engineers quarters, killing one Electrician and wounding two Engineers. She replied with her stern 6″ gun and after some 16 shells had been fired at only 4 500 yards range the battery ceased fire. When her troops were disembarked she, with the WARWICK CASTLE, WINCHESTER CASTLE and DURBAN CASTLE and several other troopships made an unescorted dash for Gibraltar. Most of the ships got through safely, but a major casualty was the beautiful P. & O. Liner VICEROY OF INDIA (1929; 19648 gr. tons), one of the pioneers of turbo electric propulsion for liners, which was torpedoed on 11 November 1942. Next day the homeward convoy sailed from Gibraltar, for England, which was reached in safety several days later.

When in July 1943 the “soft underbelly of Europe” was attacked in accordance with Churchill’s plans the LLANGIBBY CASTLE was there again. She brought a contingent of Canadian commando troops to Sicily and, in spite of bad wind and weather, saw them safely onto the shore.

In March 1944 the LLANGIBBY CASTLE was sent unexpectedly to the Clyde where she was fitted out as a Landing-Ship, Infantry (Large). Her boats had already been replaced by assault landing-craft, now she was painted in a new style of dark and light blue camouflage, and the Royal Marine Flotilla 557 embarked. The ship then sailed, via Milford Haven, for the Solent. There she and a huge number of other ships were exercised with as much secrecy as possible in night manoeuvring, anchoring in formation, shipping landing craft and, of course, signalling. She then received the troops she would carry for her greatest operations so far, the attack on Hitler’s “Festung Europa” and with them made an “invasion” of the English coast at Bracklesham. Her troops were again Canadians, the Regina Rifles, the Winnipeg Regiment and some unattached personnel. The 120 men of the Marine Flotilla party were also on board. For a week before “D-day”, the ships and their crews and passengers were isolated from shore for security reasons.

There was one more delay when bad weather on Sunday, 4 June, 1944, caused the Supreme Commander of the great invasion force, General Dwight Eisenhower, to postpone the sailing of the invasion of the fleet for one day. But on the next day the armada set forth, with the greatest number of ships under cover of the greatest number of aircraft ever used for one undertaking. The LLANGIBBY CASTLE was taking her precious cargo of about 2 500 fighting-men to “Juno” beach on the coast of Normandy. As each ship of the Southampton fleet passed the huge Nab Tower in the Solent its personnel gave a great cheer, as there was a gigantic “V” in electric lights shining towards the oncoming ships: Churchill’s “V” for Victory sign, to encourage the troops!

Following the huge flotilla of 250 minesweepers which was making certain that no hidden perils in the sea would sink any of the ships, the LLANGIBBY CASTLE and her consorts steamed in safety towards the enemy-held coast, while friendly aeroplanes prevented any possible attack by the Luftwaffe. Soon those in the ships could see the vivid flashes of gunfire and exploding bombs and shells on the coast to which they were sailing. As 05h30 next morning, as planned, the LLANGIBBY CASTLE anchored off Coursailles on the Normandy coast. At last the “Second Front”, so long discussed and longed for, was a reality.

By this time all the troops on board had already taken their places in the 18 L.C.A.’s (Landing Craft Assault) which the ship carried in lieu of her boats, and within 3,5 minutes all the landing craft were on their way to the shore. As not all o return to the ship to pick up the rest. these had to slide down canvas “Shutes” or climb down nets suspended overside, but at last all were landed. The cost: ten landing-craft eventually destroyed with the loss of 12 officers and men of the liner.

She had carried the biggest contingent to that particular part of the beach, so it was not until 14h15 that all were ashore. By 15h00 she and the rest of her division could weigh anchor and return to Southampton, where her crew could listen to the radio reports about the men she had carried.

Then came the great build-up of troops in Normandy, all of whom had to be carried over by ships. Thus the LLANGIBBY CASTLE crossed the channel more than sixty times, carrying more than 100 000 troops, a wonderful record. Incidentally, in all these operations she frequently met her former colleague in the “Round Africa” service, the LLANDOVERY CASTLE, which had been taken over for use as a hospital-ship, just as her predecessor of 1914 had been.

When peace had finally been restored the LLANGIBBY CASTLE was one of the many British liners which, after much hazardous and valuable war service, had to be refitted for her proper role. In 1946 she rejoined the Union-Castle Fleet and again sailed in the “Round-Africa” service. But newer and larger ships were built for this purpose and so in 1954 this grand vessel, once the pride of her owners, was sold to British ship breakers to produce scrap-metal for British industries.

The year after the LLANGIBBY CASTLE was commissioned the DUNBAR CASTLE was built. She looked very similar to her predecessor but was smaller, of 10 000 tons, and planned for a different use, the west cost Intermediate service between London and South and East African ports as far as Beira. She also soon became popular, being much bigger and far more luxurious than the “D” CASTLES (1904; 8 200 tons) and “G” CASTLES (1911; 7 600 – 8 000 tons) Unfortunately, her life was very short.

In January 1940 she was outward bound from London to join a convoy for Cape Town when, off Deal, she struck a magnetic mine. The explosion was so great that her back was broken. One passenger was killed, as were the Captain and two of his crew. As the water in which she sank was rather shallow, her upperworks stood up above the surface for several years until they were finally destroyed. This was a sad end to a fine ship.

Meanwhile there was talk that when the mail contract was to be renewed the British and South African governments would insist that time taken on passage between the two countries be shortened. Thus when new liners were being planned for the Intermediate Service it was decided to give them a much greater speed than had hitherto been necessary so that they could be used on mail service while the older and slower mail ships could be altered to give them the increased speed necessary to meet the new conditions, i.e. an increase from 16,5 or 17 knots to 20 knots. This also meant an increase in size. Thus the Intermediate built in 1935 ………………………………… 1936 were much larger than their predecessors.

They were the DUNNOTTAR CASTLE and DUNVEGAN CASTLE, both bearing the names of former and well-loved mailships. Of over 15 000 tons each, their speed of 16,5 knots enabled them to be used as mailships while the ARUNDEL CASTLE and WINDSOR CASTLE of 1921 – 1920 were rebuilt and re-engined. In design they were reduced replicas of the two new mail ships, ATHLONE CASTLE and STIRLING CASTLE, which were built at the same time to take the place of the old (but still very popular) ARMADALE CASTLE and KENILWORTH CASTLE of 1903 – 1904. In most respects the new intermediates were improved versions of the old LLANGIBBY CASTLE but with much better lines, a raking stern, and one funnel instead of the two squat funnels of the older ship. They were extremely good looking ships and soon became very popular. While serving in the mail service they were far superior to two of their colleagues, the BALMORAL CASTLE and the EDINBURGH CASTLE of 1910, which were of 13 360 tons and had old-fashioned reciprocating steam engines with coal-fired boilers.

When war broke out again in September 1939 the two “DUNS” were taken over by the Royal Navy and fitted out as armed merchant cruisers. The DUNVEGAN CASTLE, unfortunately, had but a short career as such, being torpedoed by a U-boat when off the West Coast of Ireland in August 1940. Her sister was released by the Navy in 1942 when enough naval cruisers had been built, and was then refitted to become a troopship, in which role she performed well until the end of the war. Thereafter she was given a most thorough refit to enable her to resume her former service. Soon after returning to the Union-Castle Fleet, however, the Intermediate Service was reformed, with all the intermediates being part of the “Round-Africa” service, three circumnavigating the continent in a clockwise and three in an anti………………….. clockwise direction. She was in the former group.

Meanwhile the Union-Castle management had decided to use South African names for ships of its fleet. Thus the next trio of ships built by Harland and Wolf’s consisted of the mailship CAPETOWN CASTLE and the intermediate DURBAN CASTLE and PRETORIA CASTLE. There is an old fort in Cape Town called “The Castle”, so that the mailship name could be easily accepted; but at first the other two names were much criticised. However, it was pointed out that in the old Union Line Fleet there had been two notable ships (for their time) called the DURBAN and the PRETORIA; thus the names of the new intermediates should be understood as a reminder of the fleet of the senior company in the Union- Castle combine.

There was, however, no criticism of the two ships themselves. The CAPETOWN CASTLE was an enlarged sister to the record-breaking ATHLONE & STIRLING CASTLES; while the new intermediates were really enlarged sisters to the DUNNOTAR & DUNVEGAN CASTLES, and also simply reduced copies of the CAPETOWN CASTLE. The difference in appearance between the 1938 trio and their 1936 predecessors was simply that the latter had two open promenade decks below the boat deck while the 1938 trio had only one, the lower one being plated over to provide more accommodation. These ships proved to be very popular. But very soon after they joined the fleet the Second World War broke out.

The DURBAN CASTLE was at once taken over as a troopship while her sister joined the R.N. to become an A.M.C. The former sailed to many places which were strange to Union-Castle ships, e.g. Halifax, India and Australia. But her most famous passengers during the war were the Greek royal family including H.M. the King, who had been brought to South Africa when their country was overrun by the Germans in 1941. Soon afterwards the DURBAN CASTLE was fitted out as a Landing Ship (Infantry) for the invasion of North Africa at the end of 1942. She was the first ship to be under fire when she led the Allied convoy into Arzeu Bay, and later took part in the attacks on Sicily and the South of France. She finished her war service by trooping in the Mediterranean.

Exciting as her war-service was it was eclipsed by that of her sister, the PRETORIA CASTLE. She had made only two trips to South and East Africa when war broke out and she was taken over by the R.N. and fitted out as an A.M.C., in which role she served until 1942. Then she was made into an auxiliary aircraft-carrier: her upperworks were cut away, a flight-deck built and, completely unrecognisable in her new form, complete with “dazzle-painting”, she served in the R.N. until 1946. Refitted for passenger-service after the war, she rejoined the company’s fleet in 1947 but under a new name, WARWICK CASTLE, the mailship of that name having been sunk in November 1942, and the name PRETORIA CASTLE being needed for one of the two mailships then under construction to replace those sunk during the war. But her new name certainly caused much confusion among travellers, as many thought she was still the 20 000 ton mailship which had been so popular between the wars.

This pair of intermediate liners was the last to be completed before the war. The next to be built was a modified sister to them, the BLOEMFONTEIN CASTLE, a name that was never popular in South Africa as it was recognised as being a “made” name out of the normal nomenclature of the line The name, however, was chosen to placate people who lived in the Orange Free State (of which Bloemfontein is the capital) as the other three provinces of South Africa each had a ship named after its chief city. The new ship was built as a “one-class” ship or “hotel ship” in which there were no longer any distinctions of first-class, cabin-class or tourist-class passengers. There was still a range of cabins of different grades to suit the pockets of people of different incomes, but the public-rooms were open to all, and thus did not need to be duplicated in two or three classes. The new ship thus carried more passengers than her half-sisters, 727 cabin class. In appearance she was completely unlike her predecessors: she had a pair of samson posts where they had the foremast, then a light foremast mounted just above the bridge, and another pair of samson ports instead of a mainmast. She differed from her half sisters also in not having a well-deck before the bridge, this extra enclosed space bringing her tonnage up to 18 400 (making her the largest intermediate vessels ever built for. the company). Her engines were H. & W. – B. & W. diesels which had been built as “spare” engines for the DURBAN CASTLE and PRETORIA CASTLE, but never used as such.

She came out in May 1950, her maiden voyage being a “Round-Africa” run London-Cape Town-Durban-Beira and then other East Coast ports. After that her service took her only to Beira (via the Cape) and then back to England. When she was planned it had been hoped that she would bring thousands of settlers from Britain to South Africa, but before she was completed General Smuts’ government had been defeated in the general election of 1948, and the new government was against bringing new settlers to South Africa from Britain. Thus the BLOEMFONTEIN CASTLE could not fulfil the role for which she had been built. The company tried to make her a popular cruise ship between Cape ports and Beira, but this also never materialised, thus it was no surprise when this “odd number” in the fleet was withdrawn from Union-Castle service to be sold. A Greek line bought her in 1959 and named her PATRIS. She thus held the unenviable record of being the Union-Castle Liner with the shortest “life” in the company, apart from those lost by accident or in war.

The Directors of the Company had, however, decided to give the plan for having a “Round-Africa” service with “one-class” ships a thorough trial, so three more vessels were ordered from Harland & Wolff’s, the RHODESIA CASTLE, KENYA CASTLE and BRAEMAR CASTLE. The last-named was welcomed as the revival of the name of a popular ship (built 1898 by Barclay Curie & Co., Glasgow, and of 6 266 tons) but the other two names were derided in England and South Africa It was bad enough to call a ship after a town without a castle (e.g. BLOEMFONTEIN CASTLE) but to call one after a country was merely stupid.

The three ships were, however, fine-looking craft, modelled on the popular DURBAN CASTLE but slightly smaller, and differing completely in having oil-fired steam turbines instead of diesel engines. They differed in appearance from the pioneer one-class ship BLOEMFONTEIN CASTLE in having two masts instead of one, and from the DURBAN CASTLE class in having no well-deck in front of the bridge, and in the mainmast being nearer to the funnel, in the position of samson-posts in the DURBAN CASTLE, these being aft in the new ships, in the place occupied by the main mast in their predecessor. They carried 526 passengers each.

Soon after the three new ships had been completed the company received complaints from passengers that the smoke from their funnels was often blown on to the promenade decks by the wind; so each ship was fitted with smoke-deflecting devices on its funnel, which detracted from their looks. Then there were complaints of the heat in the public rooms when the ships were traversing the Red Sea; so all the public rooms in each ship were fitted with air-conditioning.

These three handsome ships entered service in 1951 or 1952, bringing to six the number of ships in the “Round-Africa” service, the other three being the DUNNOTTAR CASTLE, DURBAN CASTLE and WARWICK (late PRETORIA) CASTLE. Unfortunately this service did not prove profitable, so in 1958 the DUNNOTTAR CASTLE was sold to the (American) Incres Line, renamed VICTORIA and used as a cruise ship between New York and Nassau, Bahamas Islands.

The other five ships carried on The Round-Africa service for several years but, when support by passengers dropped because of the development of faster and cheaper air-services, they also were withdrawn. The DURBAN CASTLE and WARWICK (late PRETORIA CASTLE) were the first to go, and then the latest of them all, the BRAEMAR CASTLE, which was sold for scrap in 1966.

For some time the KENYA CASTLE and the RHODESIA CASTLE maintained a joint service from East Africa via Suez to England with the KENYA and the UGANDA of the British India Line, but that did not last for very long owing to the scarcity of passengers. So the KENYA CASTLE was in July 1967 sold to the Greek CHANDRIS LINE and renamed AMERIKANIS (AMERICAN LADY) while the RHODESIA CASTLE was sold at the same time for scrapping in the Far East.

The AMERIKANIS was refitted, lengthened by 20 feet, with certain parts of her upperworks closed in, to raise her gross tonnage to 19 904. She could then carry more than double her original number of passengers.

The last ships to be built for the Union-Castle Line were actually mailships! They were the GOOD HOPE CASTLE and the SOUTHAMPTON CASTLE, which joined the fleet in 1965 under the title of “Intermediate Mailships”! They were, however, actually very fast Cargo vessels of 10 558 gross tons and as planned were to have no passenger accommodation at all. This was because of the great fall off in the number of passengers between Britain and South Africa due to the intrusion of air travel as a much faster and, later, cheaper means of travel. When these ships were still on the stocks the British Government asked the Company to provide room for a few passengers (not more than 12, to keep these twins in the category of cargo ships) so that a service to St. Helena might be kept running. I was fortunate enough to have a passage between Cape Town and Durban in each of these ships, once by myself and once as the guest of Captain “Geff” Keen, the then Marine Superintendent at Southampton of the Union-Castle Line and my late wife’s brother-in-law. He had come from Southampton in the GOOD HOPE CASTLE to test the ship’s behaviour at sea and the standard of the cargo facilities in the South African ports. I joined him at Cape Town for the trip to Durban. He warned me that, as the ship was built for speed (her diesel engines could drive her easily at 25 knots, and she had done over 27 knots on her trials) and was consequently long and narrow, she rolled rather heavily in any sea. I found, however, that even off Cape Point and Cape Agulhas her rolling was not immoderate.

She had six double cabins, all “outside” with windows (not port holes) opening on the sea and was very well fitted out. As the number of passengers carried was so small there was no dining-saloon: we all berthed with the officers in their saloon, which also doubled as smoking room with a small but very well fitted-out bar in one corner. The food served was nothing like as elaborate as it had been in the First Class in the passenger mailships but was sufficient in variety, very well prepared and extremely well served by our two stewards, who also handled the bar. We found the ships very comfortable, the only drawback being the absence of a long promenade-deck on which to do our “eight time round equals a mile” exercise. All the passenger accommodation was in the “midship house” which also carried the big funnel amidships, the bridge forward, the two ships’ boats on each side and the radio cabin. There were two short extensions aft of the bridge deck with steps forward and aft leading to the fo’c’sle deck and the upper deck aft, both of them with hatch covers, sampson posts etc, so that it was impossible to walk along them; in any case passengers were not allowed on them at all. So all we could use was the short space on the port side of the bridge (that on the starboard side was reserved for the captain and his officers). Our walks were thus of the kind we used to speak of in the Navy as “four steps and overboard”!

In 1976 the centenary of the introduction of the weekly mail service was celebrated in South Africa. The government actually had a special stamp carrying a picture of one of the Castle Line Mailships of that year, the DUNROBIN CASTLE, to celebrate this event, and it was such a popular stamp that it was sold out very rapidly. But, in less than a year later, the last ship of the Union-Castle Line left Cape Town, the GOOD HOPE CASTLE, in March 1978, thus putting an end to a mail-service which had actually started in 1854. These two ships were then sold to the Italian line COSTA ARMATORI S.P.A and renamed PAOLA C. and FRANCA C.

Absolutely splendid site, thanks ever so much.

I sailed on the Kenya Castle as a assistant steward from 24/04/1956 to 10/05/1957 i worked mainly in the dining saloon. Then met up with this ship

at Invergordon 1997 as the Amerikanis, and spent the whole day aboard her with the kind permission of her Captain. The only thing recognizable was the saloon which i thought was very small, compared to what i remembered it to be.

Forgive me if this is not the sort of comments you required, but i miss the M.N days it was a great life for one so young.

Hi James. This may be another unwanted comment, but the Kenya Castle and a dining saloon steward in the very time period that you worked there certainly brings back a childhood memory that will never leave me! I was 10 years old, and according to many who knew me then, described as a “charming boy!”. We were travelling between Cape Town and Lorenco Marques. One day while the steward was off duty, he lured me to the empty children’s playroom, and started to make passionate love to me there! I remember him to be very exited! At the time I had no idea about child molestation but was a bit startled and confused! Fortunately for me someone arrived and he let go of me! No harm was done whatsoever, and fortunately it left no enduring scars on my development as a child. It was much later before I realised exactly what happened that day! Well, that’s my Kenya Castle experience! I knew him as the steward that served our family at the dinner table. He and my dad had lots of laughs together! Was it you!? Just joking! The story however is true.

My sister and I are very keen to find a passenger list for the Windsor Castle when it docked in Cape Town in January 1939. Do you have any idea if it is possible to get one of those?

Sorry to trouble you.

Andrea Coleman

Reference is made to the Syria and a photograph (postcard) is included in the text. The text states that “The Union Line reacted to this challenge by buying the P & 0 Liner SYRIA (of 1 959 tons, built in 1863)”. It is suggested that the purchase was made in 1871. According to Duncan Hawes “Merchant Fleets” Union, Castle and Union-Castle Lines” depicts the Syria built in 1863 as having twin funnels. Can you please provide any further information on the Syria. I believe a Syria was built in 1901 (a single funnelled vessel as shown in the postcard) but I cannot find any information.

Hi

Would you have a Photo of this ship please as our family arrived in Brisbane 1880 on this ship

Regards

Rob

Dunbar Castle

A wooden full-rigged ship built in 1864 by James Laing, Sunderland. Dimensions: 182’7″×33’9″×21’5″ and tonnage: 925 GRT, 925 NRT and 817 tons under deck. The forecastle was 31′ long and the poop 60′. Equipped with iron beams. Rigged with double fore and main topsails.

1864 July

Launched at the shipyard of James Laing, Sunderland, for Duncan Dunbar. Assigned the official British Reg. No. 50071 and signal WGPB.

1866

Sold to Devitt & Moore, London. Employed in the Australian trade.

1867-1871

In command of Captain J. Swanson.

1871

In command of Captain T.F. Rowe.

1871-1873

In command of Captain D.B. Carvosso.

1873-1874

In command of Captain E.D. Alston.

1875-1879

In command of Captain J.R. Brown late of the same owner’s ship Parramatta.

1879-1881

In command of Captain A.J. Ismay late of the same owner’s ship Gateside.

1879 May 18

Collided with and sank the Swedish barque Christina off Start Point in the English Channel.

1881

Sold to Goldmeister & Ries, Bremen, and was renamed Singapore. Cut down to barque rig.

1892

Sold to German owners for £ 1800.

1899 August

Broken up.

I am searching for the passenger list of the Kinfauns Castle which docked in Durban, South Africa in April 1883.

Can anyone help, please?