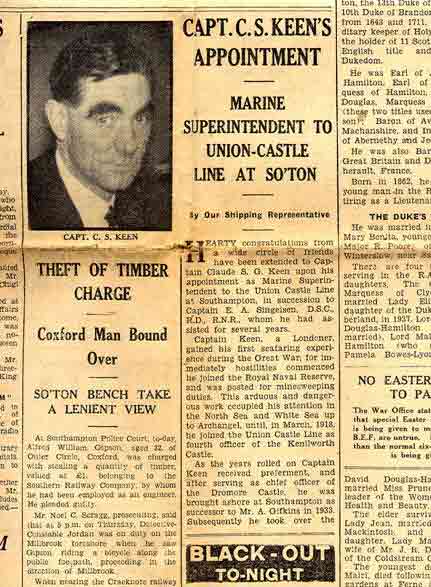

Newspaper report on appointment of Geff Keen as Marine Superintendent. Front page, Southern Daily Echo, Southampton, Saturday March 16th, 1940. (Thanks to my cousin Owen G Keen for this image - Tony McGregor)

We were met in Southampton by Captain Geff Keen, Margery’s brother-in-law and at that time the Marine Superintendent of the Union Castle Line in Southampton. He hade arranged to take his three week’s leave just after we arrived so, after we had been made comfortable in his home, he could take us around. We had a wonderful time with him, as he could get so many doors open to us which were not available to ordinary visitors.

Thus he presented me with a pass which enabled me to visit the Southampton Docks at any time for six months, which I found very useful. He then took us to Devonshire, visiting Stonehenge on the way, to stay for a week or so with his sister and her daughter. We had a lovely time with them, visiting all kinds of places on the coast or inland. Wherever we went we were struck by the greenness of the grass and the lovely flowers. We spent a long time at Lynmouth just the day before the terrible flood which washed most of the village away and drowned a large number of it inhabitants. (The flood devastated the village of Lynmouth and killed 34 people on 15 and 16 August 1952).

A thing which really enthralled me was to see real cricket on the village greens; moreover the games continued until 9:30 or 10 pm at night, as in summer in England the days are much longer than in South Africa.

Our home in Geff’s house overlooked most of Southampton harbour, so we could see the two great ships, the “Mammoths” of the way years, when they were in dock. Every Wednesday the ‘Mary’ or the ‘Lizzie’, as they were fondly called, would leave for New York, and it was grand to see them in their proper Cunard Line livery instead of the dismal ‘dazzle painting’ of way years. To me it was also lovely to hear the deep note of their steam whistles when moving in or out of harbour. Thus I was sad to learn after we had returned to South Africa that the Cunard Line had stopped them from using their sirens as some people ‘objected to the noise’! Poor Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth!

Our home in Geff’s house overlooked most of Southampton harbour, so we could see the two great ships, the “Mammoths” of the way years, when they were in dock. Every Wednesday the ‘Mary’ or the ‘Lizzie’, as they were fondly called, would leave for New York, and it was grand to see them in their proper Cunard Line livery instead of the dismal ‘dazzle painting’ of way years. To me it was also lovely to hear the deep note of their steam whistles when moving in or out of harbour. Thus I was sad to learn after we had returned to South Africa that the Cunard Line had stopped them from using their sirens as some people ‘objected to the noise’! Poor Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth!

We had a lovely day one Wednesday. In the morning Geff took us over the Queen Mary, by special permission; then took us to lunch in the Stirling Castle, which was to leave for Cape Town the next day, and then when we had had our lunch, to go on deck and see the S.S. United States entering the docks; so fast had she travelled that the paint along the waterline of her bows was almost all rubbed off by the waves. Next day I was taken over the great American ship. I must say I was very disappointed: there was no wood used in the ship’s construction, so her decks were of blue steel, with small steel studs along them to prevent people from slipping. When you went into a cabin you found that all the cupboards, etc., were of steel, so it sounded as if your clothes were being put into a filing cabinet! The furniture also was of steel, and looked very uninviting! After seeing over her I could understand why she was never popular with the Transatlantic public.

When Geff’s leave was over Margery and I went on trips all over Britain. We travelled north to Scotland via the West coast and back down to Southampton via the east coast. Wherever we went we made certain that we had tickets to get us to Southampton or money to pay for them! After each excursion we returned there and sought Geff’s advice as to what to do next.

Before we left South Africa I had joined a union of ship lovers called the World Ship Society, which had been formed several years before by a young man named Michael Crowdy. I had seen an advertisement for this society in a book that I had ordered from England. The advertisement listed the names of people in France, Canada, Australia and several others who were ‘Agents’ for the WSS in those countries, but I noticed that there was not one for South Africa. So in my letter to Michael Crowdy I had asked who its agent in South Africa was. He replied that I was the first person from my country to join, so there was not an agent for the WSS, and then asked me if I would take that post and try to advertise the Society in South Africa. This I did by writing to the editors of at least one newspaper in each of the seaports and all the main cities in our country. I had received several replies and had been able to start a branch in Cape Town before I left for England. Therefore when we had arrived in Britain I had already written to Mr Crowdy and given him my address in Southampton. To my great pleasure I had a reply from him that he and several others of the Liverpool branch of the WSS were coming down to Southampton a week or two later to visit the huge docks there, as many big ships were to be in harbour at that time, and asking me to join the party. Thus at the appointed time I was picked up by Michael and his party and we went all over the docks. This was the beginning of a friendship which started then and has now lasted for 50 years. Most of the men in this party were on the Central Committee of the WSS and I was very glad to meet them also. Some months later the Annual General Meeting of the WSS was held in London and Michael asked me to give a short talk on the progress of the WSS in South Africa. This I did, but got a great surprise when nominations were called for members of the Central Committee and Michael and another member of that visiting party put my name forward. Michael said it was policy to have at least two members of the Central Committee from overseas branches, so I was voted on, plus a member from Holland. This man was very pleased when I spoke to him in Afrikaans and was able to understand what he said to me in ‘Hollands’.

Another person I was glad to meet while in England was Dr Oscar Parkes, a former editor of that very fine annual, Jane’s Fighting Ships, one of the two Naval annuals which everyone interested in warships tries to get hold of, the other being Brassey’s Naval Annual. These books are very expensive and I had only one of each at that time, the 1914 Jane’s which had been given to me by Marischal Murray, and a Brassey for 1913, bought on the Parade in Cape Town on a Saturday morning by my cousin John Theron who was then (c. 1920) living with us in the Dutch Reformed Parsonage, Three Anchor Bay.

Oscar Parkes was the world’s expert on warships of all countries and all years since the introduction of metal-built warships, c. 1860. Besides editing Jane’s he had written many naval books and, for many years, he had written monthly articles on warships in periodicals like The Engineer and The Navy, the organ of the Navy League in Britain. He had agreed to be the Vice-President of the World Ship Society, and so was present at this AGM. He knew me by name as I had several times written to him about warships. As soon as we met at this meeting he asked me to spend a week end with him, and wrote down his address and telephone number so that arrangements could be made. Thus a couple of weeks later I boarded a bus that went from Southampton to the New Forest, and when it reached Ringwood I got off it, to find Dr Parkes waiting for me in his small car. It was not a long drive to his home, which was on a farm in amongst the trees, a beautiful place. There I met and was soon on first name status with his wife and daughter Denise. I was very interested to learn that Mrs Parkes was a daughter of a well-known commander of several ships in the Union Castle Line, Capt Maurice Randall, who was such a good artist that the Directors of the Line asked him to take a trip in each of the mail ships of the Line and to paint big ‘portraits’ of them, which were hung in the Directors’ room and other rooms in the Union Castle building. Colour photographs of all these paintings were made, and from them thousands of postcards, to be used in the ships thus portrayed. So Mrs Parkes was very pleased when I told her that I had copies of just about every one of the ‘portraits’ of ships that her father had painted.

For me, however, Oscar Parkes’ study was what I really wanted to see. It had bookcases all round the walls, each one full of hundreds of books. There were copies of Brassey’s from the first one of 1886, Jane’s from the first in 1898, the French Flottes de Combat also from its inception, c 1880, also the Italian, German and Austrian counterparts. It was really a wonderful sight. But still more wonderful was his collection of albums in which were housed tens of thousands of half-plate photographs and warships, all arranged in order of country, type, date and so on. He asked me about my collection of photographs of warships, and I had to admit that I did not have one-thousandth of what he could show me. When I told him that practically all my pictures were postcard size he said that it was far better to collect half-plate sized photographs, as he had. He just laughed when I said I could not afford it! He told me that he had photographs of every steam-driven warship in the world since 1860, except for five small river-steamers which had been turned into warships in a fierce but little-known war in South America, c. 1890.

I had a most pleasant and richly-rewarding time with the Parkes family. When it was nearly time for me to leave Dr Parkes took me to another room, his ‘store room’, in which there were many books, including spare copies of Jane’s and Brassey’s, also a number of postcard sized photographs which he kept in a drawer. He asked me to pick one of the spare copies each of Jane’s and Brassey’s, which I was very pleased to do, and also gave me several half-plate photographs and several postcard sized ones also. When I was leaving he shook hands warmly with me and said he hoped I could come again, which pleased me very much.

He was at that time busy on his ‘magnum opus’; the wonderful book British Battleships, issued in 1956. This is probably the finest book on ships ever written. In it he takes every British battleship, from the Warrior of 1860 to the Vanguard of 1946, the last of a great line. For each he gives an account of the circumstances in which the ship was built, copies of the various designs proposed and discussed until the final draft plan to which she was built. Each of these plans is beautifully drawn, with insets about changes made in each ship during her life, and so on. All particulars are given of each and a short ‘biography’ telling where and how she had served and when, where and how she had ended her career. It took him over thirty years to write this lovely book.

When I was with Oscar Parkes for the second time he showed me what he had written about Queen Victoria’s second Royal Yacht, the beautiful Victoria and Albert, designed by Sir William White, one of the greatest of battleship designers. He said that the Queen had seen a beautiful passenger ship, the City of Rome, and wanted her new yacht to resemble that ship. I took him up on this at once, because I knew something about this ship and others of the Inman Line, a Transatlantic shipping company that is quite forgotten today. I said to him that the City of Rome was a lovely ship but that she had three small funnels and four masts, quite unlike the Victoria and Albert. I said the ship must have been the Inman’s City of Paris, a bigger ship than the City of Rome but with three big funnels and only three masts. Fortunately one or other of his reference books showed pictures of the Inman liners and he saw that I must have been right. To me it was a feather in my cap to have proved Oscar Parkes wrong!

Leave a comment